This paper was initially presented at the Tales Of Terror conference, held at the University of Warwick on March 21st-22nd 2019.

The trope of the lost author is a well-worn one and there are fewer authors more lost, in all senses of the word, than Robert Murray Gilchrist.

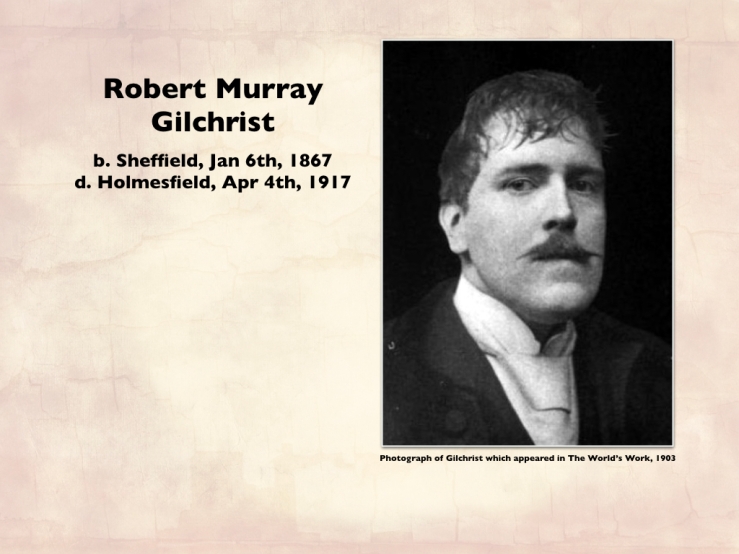

Born in Sheffield in 1867, Gilchrist was a prolific author of great stylistic breadth. By the time of his death in 1917, just before the end of the Great War, he had written over twenty novels, around one hundred short stories and a handful of histories of the greater Peak District area. Gilchrist was also well-known in society. He counted amongst his friends the likes of HG Wells and Hugh Walpole, who could trace his lineage back to The Castle of Otranto’s Horace Walpole.

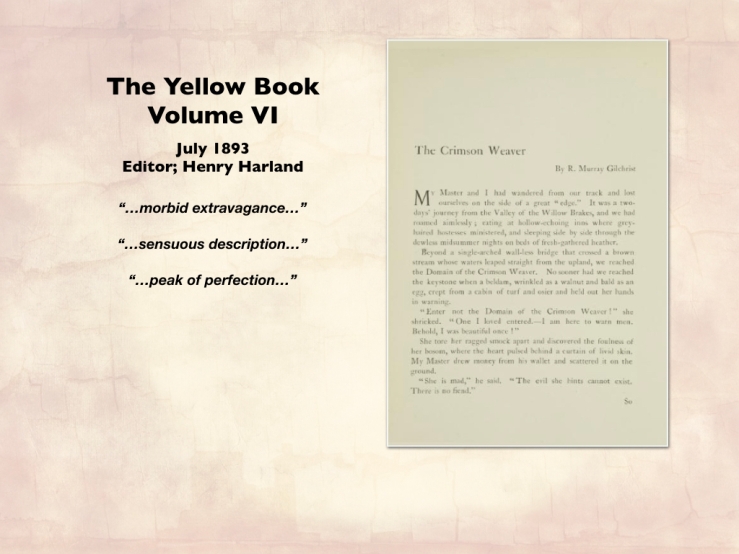

Whilst long-form works like Beggar’s Manor or The Labyrinth drew attention for their “morbid extravagance”, Gilchrist’s short stories were famed for their fantastical imagery and sinister gloom. Tales like The Basilisk or The Crimson Weaver, which was published in the sixth issue of celebrated decadent literary periodical The Yellow Book alongside tales by Henry James and Kenneth Grahame, present eerily timeless depictions of horror. The fluid view that Gilchrist had of gender and sexuality, making male characters either feeble or feckless whilst female characters are decisive and driven, also gained him notice. Although unpalatable to some audiences, The Spectator criticised Gilchrist’s works for “containing far too much in the way of sensuous description”, the author Arnold Bennett described Gilchrist’s short stories as being “the peak of perfection in that difficult genre”.

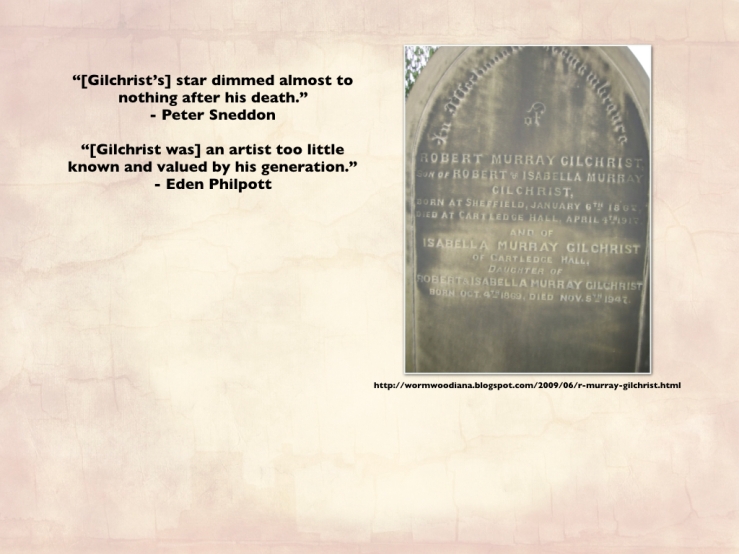

Yet, like many of his protagonists, a strange doom lingered around Gilchrist. He died suddenly at the relatively young age of fifty and, as Peter Sneddon notes in one of the few biographical fragments on Gilchrist, his “star dimmed almost to nothing after his death”. None of his novels are now in print and only two collections of his short stories are easily available to modern readers. A Night On The Moor was published in 2006 as part of the Wordsworth Tales of Mystery and Suspense series before being dropped from the roster when the series was rebranded as Tales of Mystery and the Supernatural. The Basilisk, a collection published by Ash Tree Press in 2003 which covers similar ground to the Wordsworth edition, can be found through specialist resellers at often-inflated prices. Of his historical gazetteers there is barely a trace.

Perhaps saddest of all, even Gilchrist’s grave holds no hint that he ever wrote a word of prose in his life.

The author’s friend Eden Philpott wrote that Gilchrist was “an artist too little known and valued by his own generation” and, if this is true, he has now fallen through the cracks of time to become almost completely unknown.

Why is this? A possible reason is that he simply didn’t fit the mould of what he was expected to be or, at least, didn’t fit it as well as others did. Gilchrist is lost today because he was, in many senses, lost in his own day.

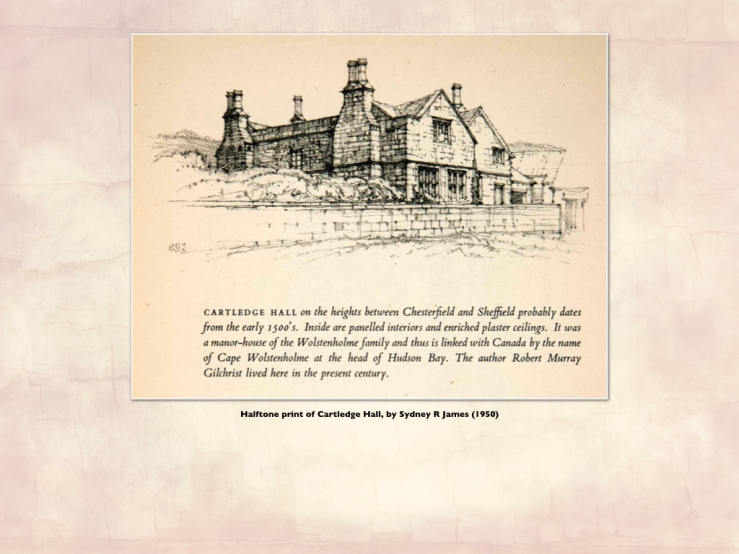

While Gilchrist, especially when one considers his short work, is often described as a decadent writer he was anything but decadent in himself. Unlike other decadents he shunned England’s cities, visiting London only occasionally, and preferred the quietness of the countryside. At the time of The Crimson Weaver’s publication, a blood-red tale which talks of “wreaths of withering asphodels” and “steaming sanguine pools”, he was living with his parents and sisters in Cartledge Hall, located in the Derbyshire village of Holmesfield. He is perhaps also the only so-called decadent who was a regular contributor to The Abstainer’s Advocate, the journal of the British temperance movement. His one truly decadent facet is that he shared the rooms in his parents’ home with George Garfitt, often euphemistically-described in biographical fragments as a “male companion”.

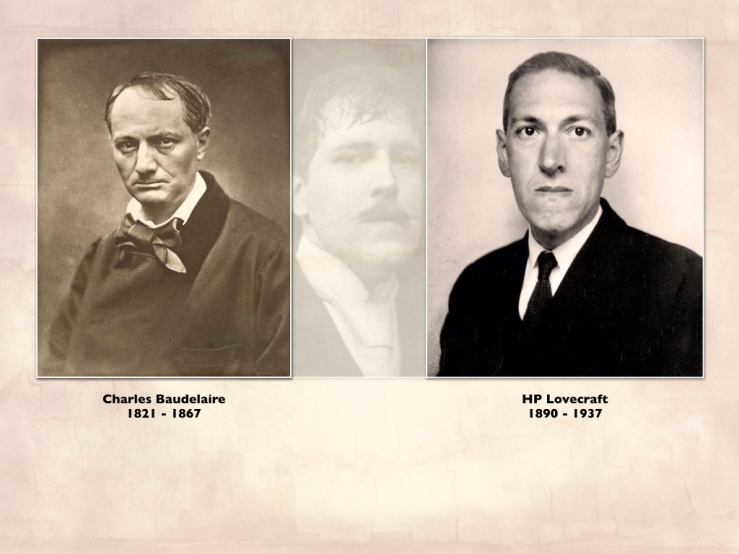

In fact, although Gilchrist’s short work does feature decadent elements and themes it is perhaps more accurate to refer to it as a precursor of that blend of the gothic, the horrifying and the eerily hallucinatory that we now call weird fiction. It is telling that the year of Gilchrist’s birth also saw the death of Baudelaire and that 1917, the year of Gilchrist’s death, saw HP Lovecraft write The Tomb, which is commonly considered to be Lovecraft’s first piece of true weird fiction. I believe there is a strong argument that Gilchrist wasn’t someone who fell into the cracks but who dwelt willingly within them, a liminal being who acted as a transition between two related modes of writing but who never fully existed in one or another.

Liminality is a phrase coined by the ethnographer and folklorist Arnold van Gennep in his 1909 work Rites of Passage and is a way of describing the transition between two separate states of being. Liminality is often understood in a way similar to this diagram, as the place where two states or ways of being transition one into the other with a period of overlap. The word ‘liminal’ comes from the Latin ‘limen’, a doorway of gateway, and it’s easy to think of liminality as a direct transition from one room to the next, one state to the next.

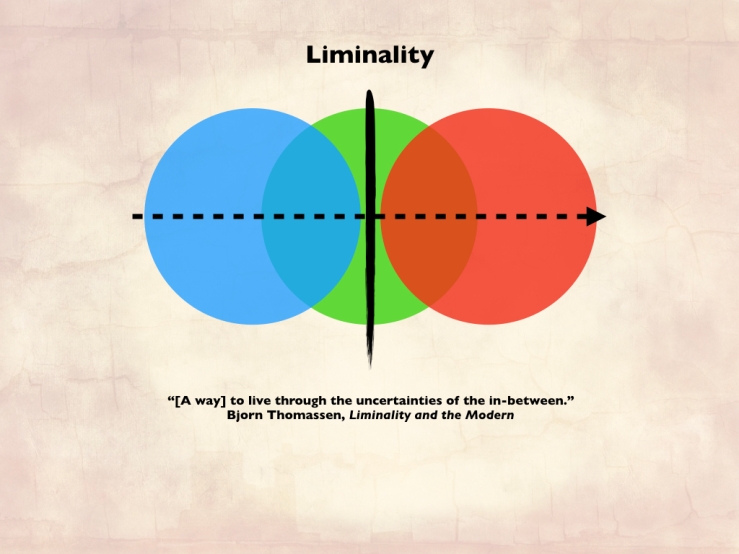

However, van Gennep used it more subtly to describe the peculiar lack of state that lies at the heart of ritual initiation; during an initiation ceremony the petitioner is neither uninitiated nor initiated but lingers at some point in between. The petitioner possesses elements of both states but exists truly in neither and rather hovers in a liminal state. Bjorn Thomassen, a modern-day scholar of van Gennep, describes liminality as a way to explain how humanity “live[s] through the uncertainties of the in-between”.

And, as much as we live through the in-between we also die through it.

Undeath, neither true life nor true death but possessing elements of each, is almost textbook liminality. Revenants and ghosts are like the living, but they are not the living. They are like the dead, but they are not the dead. I will spend the rest of this paper looking at how Gilchrist uses death and undeath not as states-in-themselves but as liminal, transitional states and how he uses this liminality to talk about his own experiences of his own world.

In “The Return”, a short story I will focus on as a case study, Gilchrist presents us with what is, at first glance, a relatively commonplace tale; an unnamed narrator leaves his beloved, the fair Rose Pascal, to make his fortune and returns years later only to find that she has passed away in his absence. So far, so gothic. Yet I feel that Gilchrist is more subtle than this and uses a number of cues to tell another story for those who wish to find it.

Our narrator returns to his home village of Halkton to find it falling into dereliction. People he once knew are now aged and distant or simply dead. He walks to Bretton Hall, Rose’s home, and he finds a woman sitting alone, surrounded by an air of weary grief:

A withered woman sat beside the peat fire. She held a pair of steel knitting needles which she moved without cessation. There was no thread on them, and when they clicked her lips twitched as if she had counted. Some time passed before I recognised her as Rose’s foster-mother, Elizabeth Carless. The russet colour of her cheeks had faded and left a sickly grey; those sunken, dimmed eyes were utterly unlike the bright black orbs that had danced so mirthfully.

Here we meet the first undead, or perhaps unliving, entity in the tale. A withered figure, shrunken and sickly, who seems oblivious to the living world and exists in a state of feeble repetition. A remnant of what was once a human being yet not quite yet a ghost. She has become a liminal figure, neither of the world nor the grave. Recoiling in horror, our narrator moves to the Hall proper and, again, finds an undead thing; a rotten and decaying building that once bustled with the life of a family home. The furniture is described as having been “once so fondly kept, now mildewed and crumbling to dust”; neither lost nor fully present. Finally, inevitably, he meets the third undead presence of the story; Rose herself.

Unlike her foster-mother, Rose is lucid and emotional; she sobs piteously as she embraces her lover. Like her foster-mother, however, she has aged:

The red-and-yellow silk shawl still covered her shoulders; her hair still hung in those eldritch curls. But the beautiful face had grown wan and tired, and across the forehead lines were drawn like silver threads.

There is a nervousness in her manner. Her speech is laced with what is described as “a wild fear”. She suddenly announces that “I no longer live in this house” before drawing the narrator away to an unhallowed place, described as “a veritable Golgotha”, where the touch of “a cold hand” sends them both into a slumber. The narrator awakens alone to find that he has been sleeping on a stone marker which informs him that:

Here, at four cross-paths, lieth, with a stake through the bosom, the body of Rose Pascal, who in her sixteenth year wilfully cast away the life God gave.

Rose is not only dead but has endured that most liminal of deaths; suicide.

This adds a shudder to The Return but, in my view, is still not the true meaning of the story. For that we will need to look slightly further.

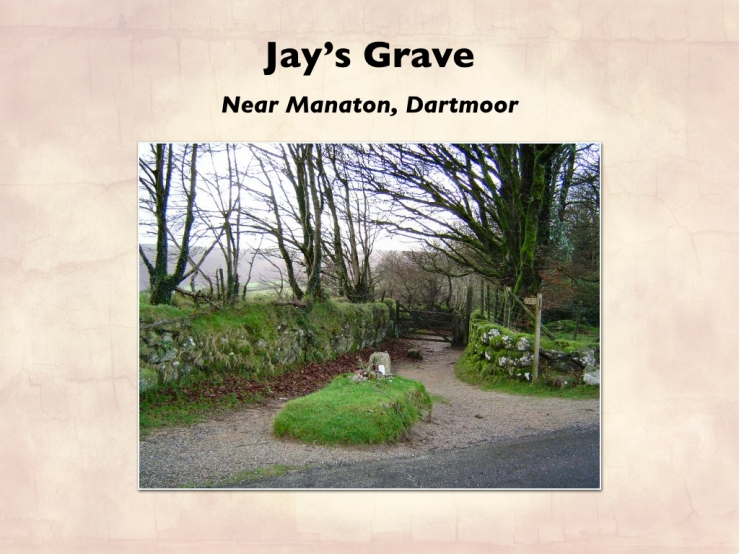

Rose is buried at a cross-roads with a stake through her heart. This is ominous yet was not unusual for the time. The grave of real-life late 18th century suicide Kitty Jay, for example, is still to be found at a cross roads on Dartmoor in Devon. Folklore held that suicides would rest uneasily in death, no longer in the living world but also not allowed to pass into the afterlife. Being buried at a crossroads was, apparently, enough to confuse the spirit and stop them from rising from their graves to haunt friends or family. Even the use of a stake can be attributed to a wish to keep the corpse in its rightful place.

However, Gilchrist’s use of one of his great foibles, mythic symbolism and especially the symbolism related to flowers and plants, makes me think that he intended Rose to be more than a simple revenant.

At the very start of The Return the narrator describes a vignette where:

[…] beneath the oldest tree stood the girl I love, mischievously plucking yarrow, and, despite its evil omen, twining the snowy clusters in her black hair.

The mention here of yarrow – also known as bloodwort, devil’s nettle, nosebleed, sanguinary and eerie – is not accidental. The plant’s “evil omen” comes from its ability to both cause and staunch the flow of blood. Not only that but excessive exposure to the plant can cause increased sensitivity to sunlight in human skin.

So, photosensitivity, imbalanced blood chemistry, a burial at a crossroads, a corpse staked into its coffin. Is The Return really a vampire story?

Yes. Well. Sort of.

Gilchrist has previous form when it comes to vampirism but it is rarely the vampirism we might expect. The Crimson Weaver, for example, uses the blood of her victims not to feed upon but to create her lustrous gowns. The Return is a story about an equally unexpected kind of vampire.

It is a story about despair.

Gilchrist, I would argue, uses the notion of undeath in The Return to talk, briefly, about how it is to be lost in despair.

Despair manifests itself in many ways, as many ways as there are sufferers, but one of its overriding elements is a feeling of hopelessness and lifelessness, of not being fully in the world. Those who despair are not dead but neither are they truly living; they exist in a liminal zone which has facets of both but is neither in their fullest states. To despair at its most abyssal ebb is to become unliving.

It is to become undead, and the undead of The Return embody this despair.

Elizabeth Carless, Rose’s foster mother, is the despair that comes from grief. She is alive but, with her soul hollowed out by the death of her daughter, appears to be far less than alive. The world is distant to her and she comforts herself with repetitious and pointless actions.

Bretton Hall is the despair that comes from loss, an emotion that is subtly different from grief. Grief is a kind of jealousy, the terror that comes from having things taken from you. Loss is more akin to envy, when others have what you do not.

Rose Pascal is the despair that comes from abandonment, which itself is a liminal lingering between grief and loss. Unlike her foster-mother, she is dead but appears alive and her actions are not repetitious but driven and intentional.

Understanding these roles allows us to see that the story becomes a kind of Gothic doubling; the path that Rose’s despair follows is then also followed by the despair of the narrator as he returns to encounter the grief, loss and abandonment that awaits him in the village. The Return becomes the eternal return of Nietszche where “the eternal hourglass of existence is turned over again and again”.

This is a suitably gloomy experience but, if I’m allowed to reach a bit, I think Gilchrist allows a ray of sunlight to pierce through.

By drawing our attention to the liminal elements in the story – undeath and despair – Gilchrist reminds us that these elements are transitory. To be liminal then they must be because liminality is, as I mentioned earlier, a transitional state. Rose’s despair eventually ends, her last act is to clutch her beloved and her last words are “you are strong”; a statement of the narrator’s physicality but perhaps also a reminder of mental fortitude. She passes from her undead state to one of true death and is finally laid to rest. Similarly, the narrator, even as he enters into his own liminal state of despair, announces “see how glad the world looks – see the omens of a happy future”.

I believe that Gilchrist’s intent, laid out in a mere six pages, is to show the inherent liminality of how we experience the world. We will journey, we will love and we will grieve. And all of this will pass. The good can become bad, but the bad will become good.

Gilchrist tells us that, even when it feels like we are locked away with nothing but our own suffering, we will one day look up and suddenly see a way out. One day we will look at the walls that kept us trapped for so long, see them fall away and say “I no longer live in this house”.

Thank you.

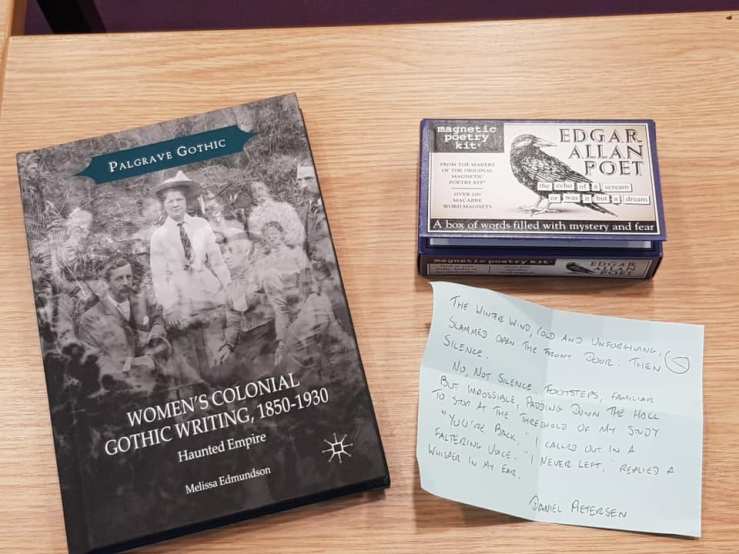

As an addendum to this post, I was very pleased to win one of the conference’s writing competitions. The brief was to write a “gothic saga in 50 words or fewer”. Predictably, my story was exactly 50 words long.

The competition prize was a copy of Melissa Edmundson’s Women’s Colonial Gothic Writing, 1850-1930 which, based on her conference keynote, will be a trove of information.

The winter wind, cold and unforgiving, slams open the front door. Then silence.

No, not silence. Footsteps, familiar but impossible, padding dow the hall to the threshold of my study.

“You’re back,” I called out in a faltering voice.

“I never left,” replied a whisper in my ear.

[…] written about him for Dead Reckonings and also used my paper at the Tales of Terror conference to focus on a vampiric interpretation of The Return, the story I read in the link […]

LikeLike